I recently acquired a little picture frame from the usual weekly source. It is very nice example, a mottled wooden frame of good proportion. Even better it was in excellent condition without bumps, knocks, scratches or peeling veneer. It has in it a faded picture of a saintly type of which there may be another posting later.

We often buy frames with the intention of reusing them. Our local framer has become used to this and even accepts that we insist on using the original piece of glass. She no longer resists, perhaps because of the sheer volume of work that comes her way from our runway picture buying habits.

The best old frames are empty ones or those with indifferent or damaged artworks inside, as they don’t command much of a price. Usually I take the old picture out fairly quickly and start sizing up new occupants, either unframed works or pieces purchased in unattractive modern frames. There isn’t always an immediate match and there is a pile of frames in the garden shed and another accumulating at the back of the hall awaiting the right work.

There were two obvious candidates for this frame. A lovely little wash drawing by the Reverend William Gilpin, set in an expanse of white surrounded by a thin narrow frame, or a John Absolon pen and ink drawing. This work is matted in a dark grey green and framed in the same type of narrow wooden frame. Both of these works came from the same sale, so they may have even once hung in the same house. Yet here they have not exactly been star attractions. The Gilpin hangs in my dressing rom and the Absolon has been stuck down the side of a large wardrobe, really due to its indifferent framing.

So which of these two works would get to emerge into the light in a new glossy frame of significant proportion and perhaps end up hanging in the library?

1.

The short answer to this is (and there was much discussion) is the Absolon. Although the stark black and white nature of the Gilpin suited the frame, so did the sepia tones of the Absolon. In the end the current state of the Absolon, meaning that it had never made it to the wall, meant that it came up tops for rescue.

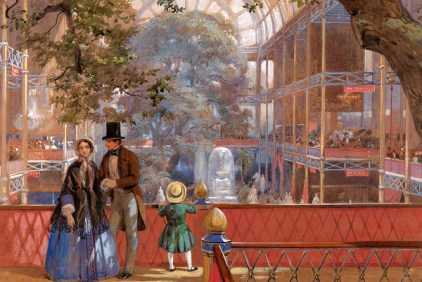

John Absolon’s (1815-1895) claim to fame, at least in this household, are his beautiful depictions of the interiors of the Crystal Palace exhibition.

These watercolours really are how most us know how the Great Exhibition of 1851 looked. The soon to be reframed drawing is not sadly one of these but a group of women in a tent. I like to think its something to do with Florence Nightingale – I know not why.

So the Absolon duly departed to the framers from whence it’ll be back in 3 – 4 weeks with a generous double mount in off white, original glass and the newly found frame. The Gilpin was scheduled to return to the darkness of my dressing room. However somehow it got stuck half way and came to rest lodged in a chair in our bedroom and there it stayed.

2.

It is a funny thing but when you live in a house full of objects a simple reshuffling or the transportation of an item from one place to another can bring to it renewed attention equivalent and perhaps even greater than that it received on arrival

I now find myself looking at the Gilpin out of the corner of my eye all the time. Is it reminding me to finish its journey back to the dressing room wall or reproaching me for failing to choose it for star treatment? After all William Gilpin is a far more important artist than is poor old John Absolon even taking the Great Exhibition into account.

This little wash drawing is perhaps the oldest artwork in my collection. Gilpin who was born in 1724 and died in 1804 is really an eighteenth century, rather than a nineteenth century artist. In the object timeline of this house he sits alongside my Hester Bateman port label and a George II chair my cat has personally adopted as his favorite sleeping place – probably because the seat sags.

Reverend William Gilpin is not now well-known – who of real interest is? But he is/was for a long time considered the father of the picturesque. Gilpin, who wrote an early book on gardens, A Dialogue upon the Gardens … at Stow in Buckinghamshire (1748), was one of the first to get excited by such things as rugged, wild scenery. Until then people were more inclined to gaze ecstatically upon organized landscapes – ether those organized for work or those organized as symbols to the achievements of man. Because of this Gilpin is one of the key originators of the idea that we should manipulate landscape images (and eventually the landscape itself) into aesthetically pleasing although seemingly accidental forms.

When it came to painting, Gilpin believed that composition should work as a unified whole, incorporating several elements. These were ‘a dark foreground with a front screen or side screens, a brighter middle distance, and at least one further, less distinctly depicted, distance.’ He believed a ruined abbey or castle would add ‘consequence,’ regardless of whether there was one in the view being depicted.

Gilpin knew that nature was good at producing textures and colours, but he considered it was rarely very good at creating perfect compositions. For a perfect composition, some extra help was required from the artist, perhaps in the form of a carefully placed tree, castle, ruin etc. His became a much copied formula.

So this little picture sits there on my chair – proudly claiming its picturesque properties. Revered Gilpin isn’t only the earliest painter in my collection but he is probably the most important. He was an ideas man, an originator and a key spokesman for a particularly important way of thinking about art. This little drawing does exactly that. Like all his works it is a lesson in this theories, with a bright middle distance, a side screen of trees and, an oh so carefully placed, ruined castle tower.

What I like about the Gilpin now I’ve been watching it for a week is that this landscape is a made up place – there is nothing real about the scene. Gilpin said his works were designed ‘to explain the country rather than to give an exact portrait of it.’ The place might be a fake but what is real is the feel of it and the satisfaction that emanates from this really rather tiny composition. This little imagined landscape provides a depth of engagement, thus this week’s repeat glances, that can only come from looking at a really good, albeit small, work.

On another level Rev Gilpin’s little missive has worked its charm on me. It has been picked up from the chair, and rather than returned to the dressing room, it has made its way to the library wall. There it awaits the arrival of the John Absolon.