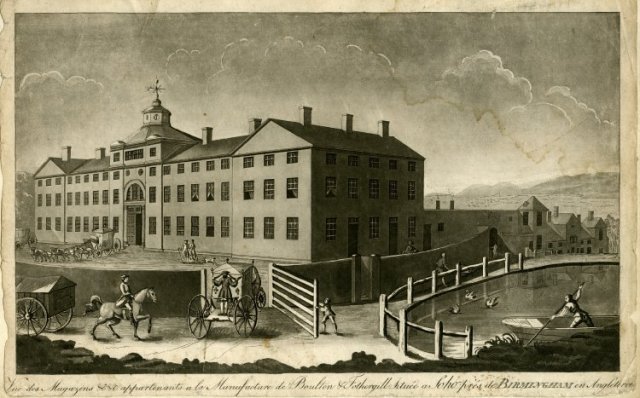

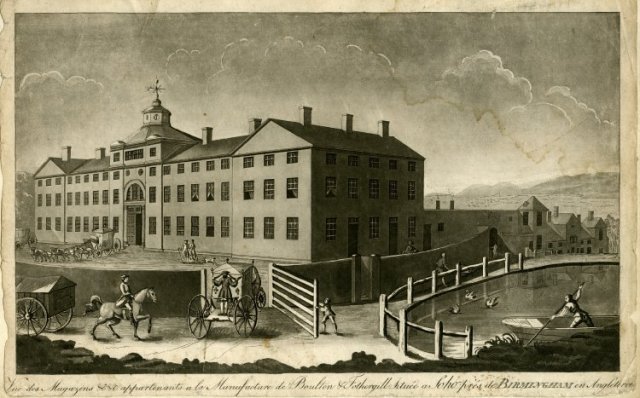

Matthew Boulton’s Soho works Birmingham (c1795)

The other day while looking at an Old Sheffield Plate salver, a friend identified the marks, a pair of suns, as those of Mathew Boulton. Boulton was, he said, ‘a highly regarded Sheffield plate maker.’ I was fascinated. Why was Boulton called a Sheffield plate maker rather than a silversmith? Was there some distinction to be made? Didn’t most silversmiths just segue into Sheffield plate-making once the technology changed? Was there really a hierarchy of Sheffield Plate makers about which I knew nothing?

1.

Matthew Boulton (1728-1809) Artist Unknown.

Matthew Boulton was, it turned out, a name I’d come across before but not quite absorbed. Born in 1728, he was the son of a Birmingham manufacturer of small metal products (significantly not a silversmith). Matthew inherited the family business while in his early thirties and expanded the firm, branching into new technologies including fused silver plate – what we now call Old Sheffield Plate.

What catapulted Boulton to international fame was a debt. Boulton was owed money by one John Roebuck who offered his shares in a new invention. That invention was James Watt’s steam engine. Boulton & Watt went on to provide steam engines for factories and mines across England, powering the Industrial Revolution and becoming immensely rich as a result.

Boulton built a large steam-powered factory, the Soho works, in Birmingham, to make among other things ‘plated wares.’ The factory became one of ‘the show places of Britain in which England had national pride’ and distinguished visitors from abroad flocked to see this wondrous manufactory and to acquire its works.

Matthew Boulton was a member of the Lunar Society, a group of men prominent in the arts and sciences. Members included James Watt, Erasmus Darwin, Josiah Wedgewood and Joseph Priestly. The Society met each month near the full moon, often in Boulton’s home and are credited with developing concepts and techniques in science, agriculture, manufacturing, mining, and transport important to the spread of the Industrial Revolution.

Matthew Boulton’s marks, dual suns, seen here on a candlestick.

So there was Matthew Boulton and his Sheffield plate, at the very centre of the Industrial Revolution in exactly the same way as was Josiah Wedgewood and his pottery. This is in part what makes late Eighteenth and early Nineteenth century decorative arts so fascinating. There was an enormous amount of innovation and technological advancement going on most of which was focused on providing new and better items for the home.

The friendship between Matthew Boulton and Josiah Wedgewood suggested to me the potential for a nicely knowing dinner table pairing of Boulton plate and Wedgewood ceramics. So I set about re inspecting our pieces of Old Sheffield plate looking for marks, well, let’s be frank: looking for Matthew Boulton’s marks.

2.

The marks on Old Sheffield plate have always seemed slightly impenetrable. The system lacks the clarity and simplicity of the hallmarking system for sterling silver (which is pure genius). Hallmarks are essentially a signature whereas Sheffield plate marks were an early form of corporate branding. When previously I’d looked at books dedicated to Sheffield plate I’d been further discouraged by the dates associated with marks, which seemed ancient and unlikely to be encountered.

In 2013 we blogged about finding a copy of Elsie de Wolfe’s The House in Good Taste, in a box lot. Along with that had come a copy of Old Sheffield Plate by R A Robertson and The Silver & Sheffield Plate Collector by W A Young. After examining the photographs, these books had been filed away on a shelf. Turning to them now I discovered in Robertson one of those delightfully engaging experts with an encyclopedic knowledge and a humorous approach to his subject.

Most of our pieces of Sheffield turned out to be unmarked. Marking Sheffield was optional and often frowned upon by retailers who feared that marks allowed customers to compare prices across competing shops. The four numbers that appear on some Sheffield are seldom dates. So the 1832 discovered on one of my candlesticks are more likely a stock number.

The centre of an Old Sheffield Plate salver by J. Dixon & Co., see ‘The great silver rush of May 2013.’

The first legitimate mark I encountered was on a small salver, itself the subject of an earlier blog (The great silver rush of May 2013). The marks were of J. Dixon & Co of Birmingham, first registered in 1784 of which I’ve been able to discover very little additional information. This doesn’t mean the salver is from 1784; the dates on Sheffield are those when the mark was first recorded – there is no yearly update as with silver. With Robertson’s advice as to style I suspect that the dish is almost 40 years later, the 1830s, once borders of grapes came into fashion.

The next mark (a bell) turns out to be the work of Roberts, Cadman & Co. Samuel Roberts, also from Birmingham, is one of the other great innovators of Old Sheffield Plate and was undoubtedly a close rival of Mathew Boulton. Robertson makes Samuel Rodgers out to be an interesting character and describes his personality in unflinching terms –

‘Samuel Roberts had the feeling of an artist and the gifts of a craftsman united with commercial aptitude. … His zest for life and his tremendous mental vigour made him interested in nearly everything; and a forcefulness of character combined with a practical sense gave him the power to succeed in what every he set his hand to.’

‘Few men have the character to remain unspoiled by success such as his and he was not one of them. The sun of his sterling qualities had spots. He was a little vain, a little smug and was beset of a Smilesian priggishness that was impatient of others less gifted than himself.’

“He always succeeded in being in advance of all his competitors, none of whom has genius that could compare with this. His competitors apparently awaited his productions, before deciding on what line their own goods were to take shape. The quality of his plated goods and the correctness of their outline were excelled by none and equaled by few. Mathew Boulton being a rival of his amongst the makers of note of the time.”

Samuel Roberts mark, a bell, on a pair of candlesticks by Roberts Cadman and Co.

My Samuel Roberts marks are on a chaffing dish which again I suspect dates for the 1830s. It’s not a period of design that Robertson (or his generation) much like (he’s far more Queen Anne, Robert Adam, or Regency focused). He tends to dismiss Roberts Cadman’s later works and anything else of the William IV period. I however am clinging to this remark – ‘Samuel Roberts must be reckoned one of the great figures of Old Sheffield plate manufacture.’

Roberts was based in Birmingham but didn’t much like what he saw around him. R A Robertson has such a distinctive turn of phrase I can’t resist one more quote that points at least in the direction of our target Matthew Boulton. Roberts writes –

Samuel Roberts, from some lofty pinnacle of moral rectitude, looked down on Birmingham, that horrid hotbed of lazy workmen turning out tenth rate trash.

But as Robertson assures us although Birmingham was turning out a prodigious quality of the cheap and nasty there were exceptions – the most notable being Matthew Boulton – ‘equal to Roberts in his own fields and superior in everything else.’ Ouch– take that Samuel Roberts.

Roberts Cadman & Co, Chaffing Dish (c1830)

3.

Circling around the Old Sheffield plate here, checking for marks, never did bring me to Mathew Boulton’s pair of suns. Like most groups or collections of things here, it’s not a specifically curated collection. I’ve just assembled a few pieces of Old Sheffield because I like its qualities and its usability. But R A Robertson and his charming book Old Sheffield Plate has made me think a little differently.

Robertson is so enthusiastic about the craft aspects and the inherent innovations of this comparatively short lived process, that it seems an art-form to which one could pay a little more attention. Pairing old friends Wedgewood and Boulton on the dinner table remains a new goal. In the meantime knowing a little more about Samuel Roberts and his personality, I can’t wait for the arrival of a Boulton work and to see what transpires when two Old Sheffield Plate making rivals are similarly reunited on the table

DLJ